Anyone who has led a newsroom as long as I have in Cleveland can’t help but have an impact on the content published on our many platforms, including cleveland.com and The Plain Dealer.

Some readers wish I’d never set foot in the city, judging by my mail. Others are more complimentary. But whether you’re a fan or a detractor, you can probably blame a Floridian named Jim Clark for my being here.

He died last month, and I’ve been thinking about him and the lessons he offers for modern journalism.

I was 25 when I met him. I’d been a reporter at three newspapers — a South Jersey weekly so old it had covered George Washington, a tiny daily in Dover, Del., and Cleveland’s sister paper in Harrisburg, Pa. Jim was the recruiter for the Orlando Sentinel, recently rated one of America’s best papers. I sent him my resume, and to my surprise, he called to invite me down for interviews. I soon had a job.

At 25, I still had the imposter syndrome common in your 20s, and walking into the Sentinel newsroom did nothing to abate it. The place had the biggest collection of stellar journalists I’ve ever seen. Hard-charging reporters. Poetic writers. Editors who knew how to nurture and inspire. Looking around, I wondered how Jim Clark could see me in that company.

Because of the people who surrounded me in that newsroom, I became a fully fledged journalist there. Teaming up with a brilliant reporter named Jim Leusner helped make me more inquisitive and resourceful. Editors like Greg Miller, David Porter and Barry Glenn helped me see holes in my reporting.

And always, the writing. Reading some of the work from my colleagues left me awed, and talking to them about their approach never failed to enrich. I wanted to stand with them.

We had something called the ‘lead bank’ for those days when you’d written three stories and were so weary you couldn’t find the perfect opening for a fourth. You’d call out for help, and within seconds, a half dozen colleagues would start tossing out ideas like popcorn, each one refining and building on the last until the perfect lead emerged.

I loved those days. In Orlando I started working with Mark Vosburgh, launching a partnership that lasted a quarter-century in Florida and Cleveland.

Like I said, Orlando was loaded with talent, and Jim had recruited them all. Most newspapers had recruiters like him back then, scouting talent nationwide. Another was Arlene Morgan at the Philadelphia Inquirer, where I thought I’d end up. I never made her cut, so you can blame her, too, for my being in Cleveland.

Jim didn’t edit stories or manage anyone. His job was to find the best and win them over. He also hosted a newsroom poker game, and I’ve said ever since that reporters can find no better training. Like reporting, poker is about reading people—knowing when someone’s bluffing and when they’re not. Jim’s monthly games were master classes in human nature.

When I told Mark that Jim had died, he instantly went to the same memory I had—Jim humming a Christmas carol during the game. Even though poker is about bluffing, Jim never did. When he held three kings, he hummed We Three Kings—and won anyway. Jim understood human nature. He knew some reporters with fragile egos couldn’t accept they were being bluffed, so they’d call him even when he telegraphed his hand. Every time, they thought this would be when he’d start bluffing. He raked in their chips.

His understanding of human nature is what made him so good at recruiting, I suspect. He did the requisite checking of backgrounds of candidates, but I think he knew how to read between the lines to spot diamonds in the rough. I’ll never understand what he saw in me, but I’m forever grateful he did.

As newspaper fortunes soured, recruiters became a luxury many papers couldn’t afford. After he left the Sentinel, he taught college students and wrote books about Florida history and politics. He became a regular presence on local television as a well-known analyst.

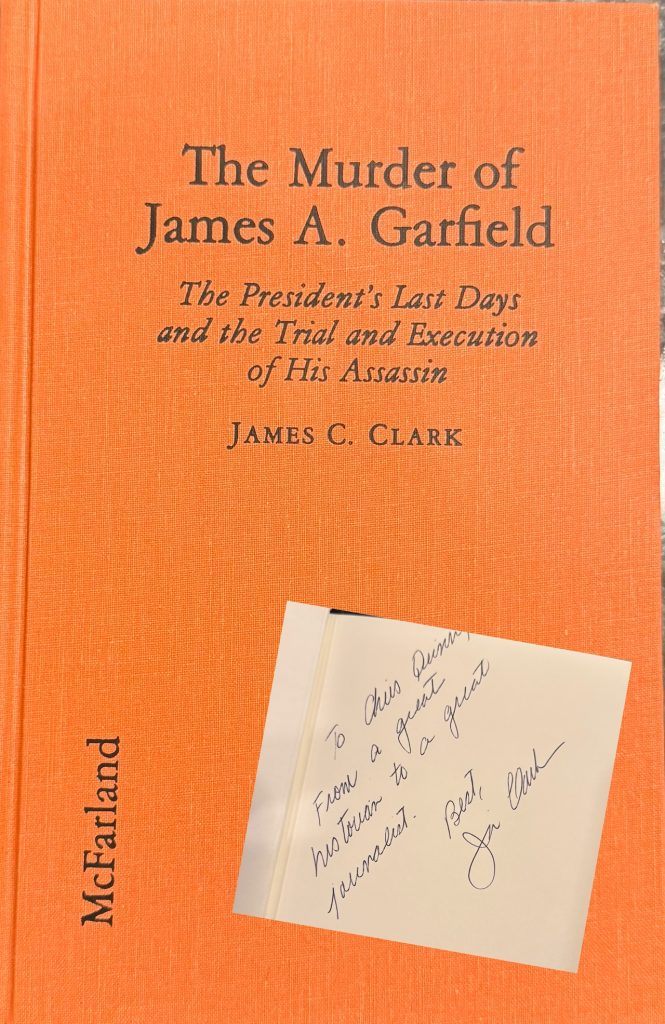

He had one tie to Northeast Ohio—President James A. Garfield. Long before Netflix’s Death by Lightning recently revived interest, Jim had written The Murder of James A. Garfield (1993), about the assassin and Garfield’s death from sepsis. I still have my signed copy. He was already shifting to history writing before I left Orlando.

I wonder how Jim would approach recruiting today. We no longer have the kind of farm system that helped me grow. Many smaller papers where young reporters once cut their teeth have closed, and those that remain rarely have time to develop talent.

I wasn’t close to ready for Cleveland when I started out. I needed that farm system.So where would Jim find someone like me today? Who are we missing now who could come in and light a fire? Recruiting may be journalism’s biggest modern challenge, as many college programs still train students for newsrooms of the 1970s.

I’ll bet Jim would have had ideas. I wish I’d picked his brain while I still could—and thanked him properly for helping a young reporter find his place in the herd.

If you purchase a product or register for an account through a link on our site, we may receive compensation. By using this site, you consent to our User Agreement and agree that your clicks, interactions, and personal information may be collected, recorded, and/or stored by us and social media and other third-party partners in accordance with our Privacy Policy.